The Math That Decides Your Fate

#You are sitting across from a venture capitalist in a room with glass walls. The coffee is expensive. The chairs are ergonomic. The vibe is friendly.

They offer you one million dollars.

It feels like a victory. You shake hands. You call your partner. You feel like you have won the lottery.

But you haven’t won anything yet. You have just sold a piece of your machine.

Most founders treat fundraising like a revenue event. They see the cash hitting the bank account and they celebrate.

But mechanically, fundraising is a sale. And every sale has a cost.

The cost is dilution.

Dilution is the boogeyman of the startup world. Everyone warns you about it. Everyone tells you to guard your equity with your life.

But few people explain the actual physics of how it happens or why it might actually be the only way you survive.

We need to open up the cap table and look at the engine.

The Illusion of Control

#Imagine you have a pizza.

This is the analogy everyone uses. But, it is a bad analogy.

A pizza is static. If I give you a slice, I have less pizza. I am hungry. You are full. It is a zero sum game.

A startup is not a pizza. Maybe it is a balloon…

When you start, the balloon is deflated. It fits in your pocket. You own 100% of the latex.

When you take investment, you are selling a percentage of the balloon in exchange for the air required to inflate it. To make it bigger.

You might own a smaller percentage of the surface area, but the volume of the balloon has expanded massively.

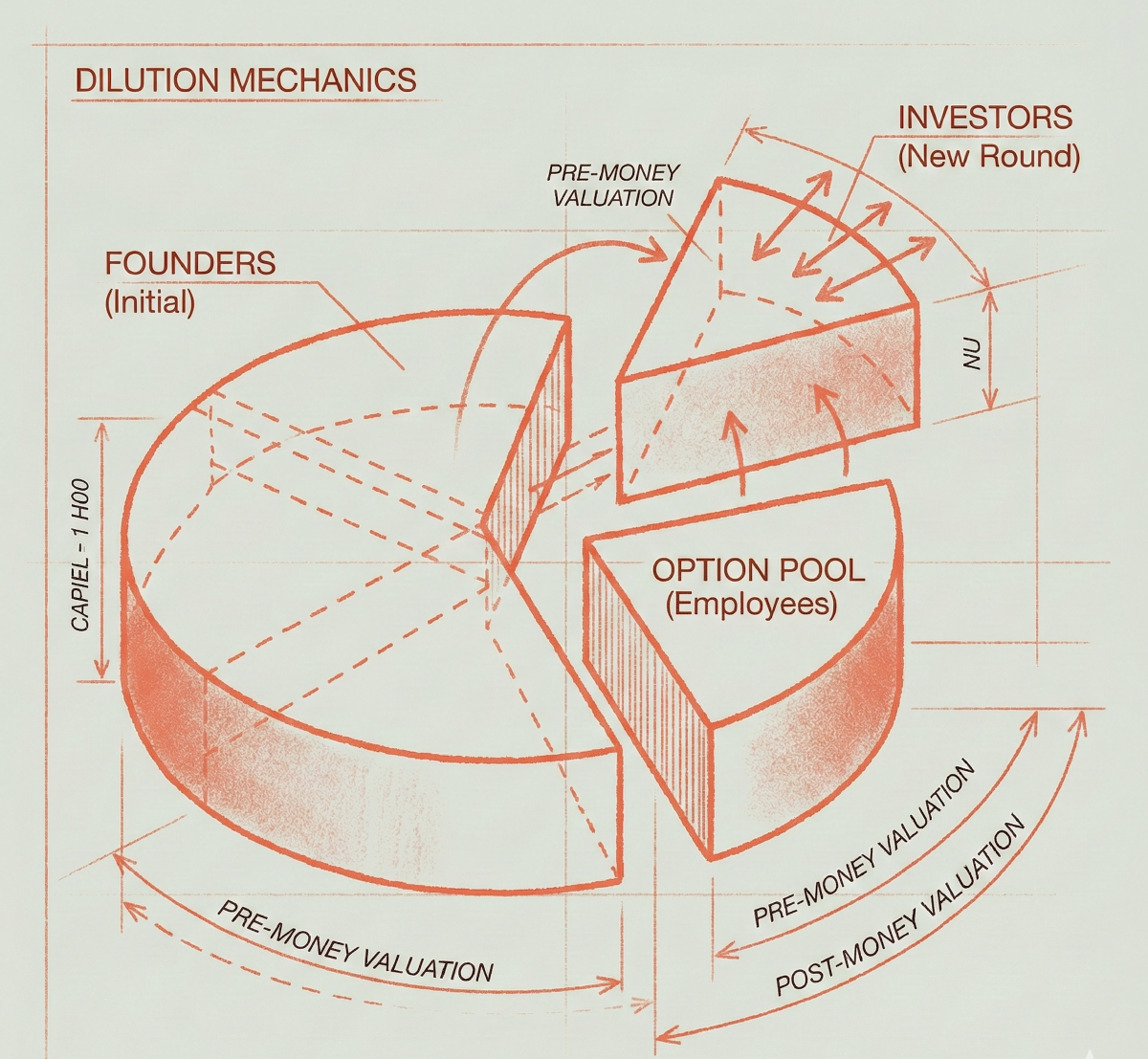

This is the core concept of dilution. You are trading ownership percentage for capital growth.

But how do we measure that trade?

We use two numbers that sound simple but dictate everything: Pre-money and Post-money valuation.

Let’s look at a concrete scenario.

You have bootstrapped your company. You own 100% of the shares.

An investor wants to put in $1 million.

They say your company is worth $4 million right now, before they write the check.

That $4 million is your Pre-money Valuation.

The math is simple addition.

Pre-money ($4M) + Investment ($1M) = Post-money Valuation ($5M).

The investor’s ownership is calculated based on the Post-money.

$1M divided by $5M equals 20%.

So, after the deal closes, the investor owns 20% of your company. You own 80%.

You have been diluted. You used to own everything. Now you own four-fifths of everything.

But look at the value.

Before the deal, you owned 100% of a company worth, theoretically, $4 million. Your stake was worth $4 million.

After the deal, you own 80% of a company worth $5 million. Your stake is roughly worth $4 million. Wow.

On paper, you haven’t lost value. You have just reorganized it.

And now you have a million dollars in the bank to hire engineers. That’s the impact.

The Valuation Trap

#Here is where the story usually gets complicated.

Founders have egos. Investors have mandates.

Founders want the highest valuation possible. It feels like a score. It validates that their idea is brilliant.

If an investor offers you a $4 million Pre-money, you might fight for $6 million. Or $8 million.

Let’s say you are a great negotiator. You convince them your company is actually worth $9 million Pre-money.

They put in $1 million. The Post-money is $10 million.

The investor now only owns 10% ($1M / $10M). You kept 90% of your company.

You feel like a genius. You minimized dilution. You protected your stake.

But you may have just set a trap for your future self.

Valuation is not a reward. It is a benchmark. It is a promise of future performance.

When you raise money at a $10 million Post-money valuation, you are effectively promising that you can grow the company significantly beyond $10 million before you need more cash.

The next time you raise money, usually 18 months later (that is the expectation), the new investors will expect to see growth.

They want to see that the value has doubled or tripled.

If you raised at $10 million, your next round needs to be at $20 million or $30 million to make everyone happy.

That requires massive revenue growth. It requires perfect execution. It requires luck.

Now consider the alternative.

What if you had taken the “worse” deal?

What if you accepted the $4 million Pre-money?

Your Post-money was $5 million.

For the next round to be a success, you only need to hit a valuation of $10 million or $12 million. And you have the same amount of cash in the bank to do it.

That is a much lower hurdle to clear.

By taking the lower valuation initially, you gave yourself breathing room. You lowered the bar for success.

This is the counter intuitive truth of dilution.

Sometimes, taking more dilution early (accepting a lower valuation) increases your probability of success later.

Taking less money, or raising at a lower valuation, means you don’t have to be a unicorn within twelve months. It means you can build a sustainable business without the crushing weight of impossible expectations.

The Down Round Disaster

#What happens if you miss the bar?

Let’s go back to the scenario where you negotiated that $10 million valuation.

Eighteen months pass. You grew, but you didn’t grow enough. The market cooled. Competitors emerged.

You are running out of cash. You need to raise more money to survive.

But new investors look at your numbers and say, “This isn’t a $20 million company. This is a $5 million company.”

You are in trouble.

Your last round was at $10 million. The new round is at $5 million.

This is a Down Round.

Mechanically, this destroys your ownership percentage through pure volume.

To understand this, we have to look at the Share Price.

In your first round (the high valuation), let’s say you sold shares at $1.00 per share.

Now, because the valuation has been cut in half, the new investors are buying shares at $0.50 per share.

You need to raise another $1 million to keep the lights on.

If the price was high ($1.00), you would only need to create and sell 1,000,000 new shares.

But because the price is low ($0.50), you have to create and sell 2,000,000 new shares to get the same amount of cash. (Selling each share at the share price to raise those funds)

This is the mechanical punishment.

Because the company is worth less, you have to print way more stock to buy the same amount of money.

This floods the cap table.

Your slice of the pie shrinks rapidly because the total number of slices is exploding.

If you had raised at the lower valuation initially, the share price would have started lower, but the growth slope would be positive. You would be selling fewer shares in the second round because the price would be going up, not down.

The Pool Shuffle

#There is one more variable we have to put on the table.

Employees.

You cannot build a company alone. You need to hire talent. And since you cannot pay them market salaries yet, you pay them with equity.

This comes from an “Option Pool.”

Typically, investors will demand that you set aside 10% to 20% of the company’s equity for future employees.

But here is the trick.

Investors usually insist that this option pool is created before their investment counts.

They want it to come out of the Pre-money valuation.

Let’s look at the math again.

$4M Pre + $1M Investment = $5M Post.

The investor gets 20%.

But if they require a 10% option pool calculated in the pre-money, the math changes.

The Post-money is still $5 million. The investor still has $1M worth of shares (20%).

But the 10% option pool ($500k value) has to be carved out of the original $4M.

So now, the founders don’t own the full $4M pre-money value. They own $3.5M. The other $500k is sitting in the empty bucket waiting for employees.

The investor didn’t get diluted by the option pool. You did.

You effectively paid for the future employees out of your own pocket before the investor arrived.

This is standard practice. It is not necessarily malicious. But it is a mechanical reality that surprises many founders.

Navigating the Machine

#Equity is not just a number on a spreadsheet. It is a relationship map.

Every percentage point represents a person or an entity that has a claim on your future.

When you understand the mechanics of pre-money and post-money, you stop looking at valuation as a vanity metric.

You start seeing it as a lever for risk.

When you understand the danger of down rounds, you stop trying to maximize every deal and start trying to optimize for momentum.

You realize that a “fair” valuation that allows you to easily triple your value in the next round is better than an “amazing” valuation that requires a miracle.

And when you understand the option pool shuffle, you realize that hiring plans are not just HR issues. They are capital structure issues.

The goal is not to hoard 100% of the company.

The goal is to be the captain of a ship that actually reaches its destination.

If you have to sell parts of the hull to buy fuel, do it. But make sure you bought enough fuel to get to the next port.

Because if you run out of gas in the middle of the ocean, it doesn’t matter how much of the ship you own.

You own 100% of a shipwreck.