There is a grim thought experiment that circulates in software engineering departments.

It is morbid, but it is necessary.

Imagine your lead engineer steps off the curb tomorrow morning and gets hit by a bus.

Or, to use a less tragic but equally disruptive example, imagine they win the lottery. Imagine they decide to move to a cabin in Montana with zero internet access. Imagine they simply quit without notice.

What happens to your company the next day?

Does the code stop shipping? Does the sales pipeline freeze because only one person has the relationships? Does the bank account get locked because only one person has the two-factor authentication device?

If the answer to any of these questions is yes, you have a Bus Factor of one.

This is a critical vulnerability.

In the early stages of a startup, a Bus Factor of one is inevitable. You are the founder. You do everything. If you disappear, the idea disappears.

But as the organization matures, retaining a Bus Factor of one is not a badge of honor. It is a structural defect.

It means you have built a fragile system that relies on specific individuals rather than resilient processes.

The Illusion of Efficiency

#Why do we allow this risk to persist?

Usually, it is because we prioritize speed over resilience.

It is faster for one person to know everything about a specific domain. If Jane is the only one who understands the legacy billing code, she can fix bugs in it faster than anyone else. She does not have to explain it. She just does it.

If we ask Jane to stop coding and teach Bob how the billing system works, velocity drops. Jane is annoyed because she is not shipping features. Bob is annoyed because he is learning a boring system he does not own.

On the surface, this looks like inefficiency.

But we need to reframe how we view this time investment.

We are not paying for redundancy. We are paying for insurance.

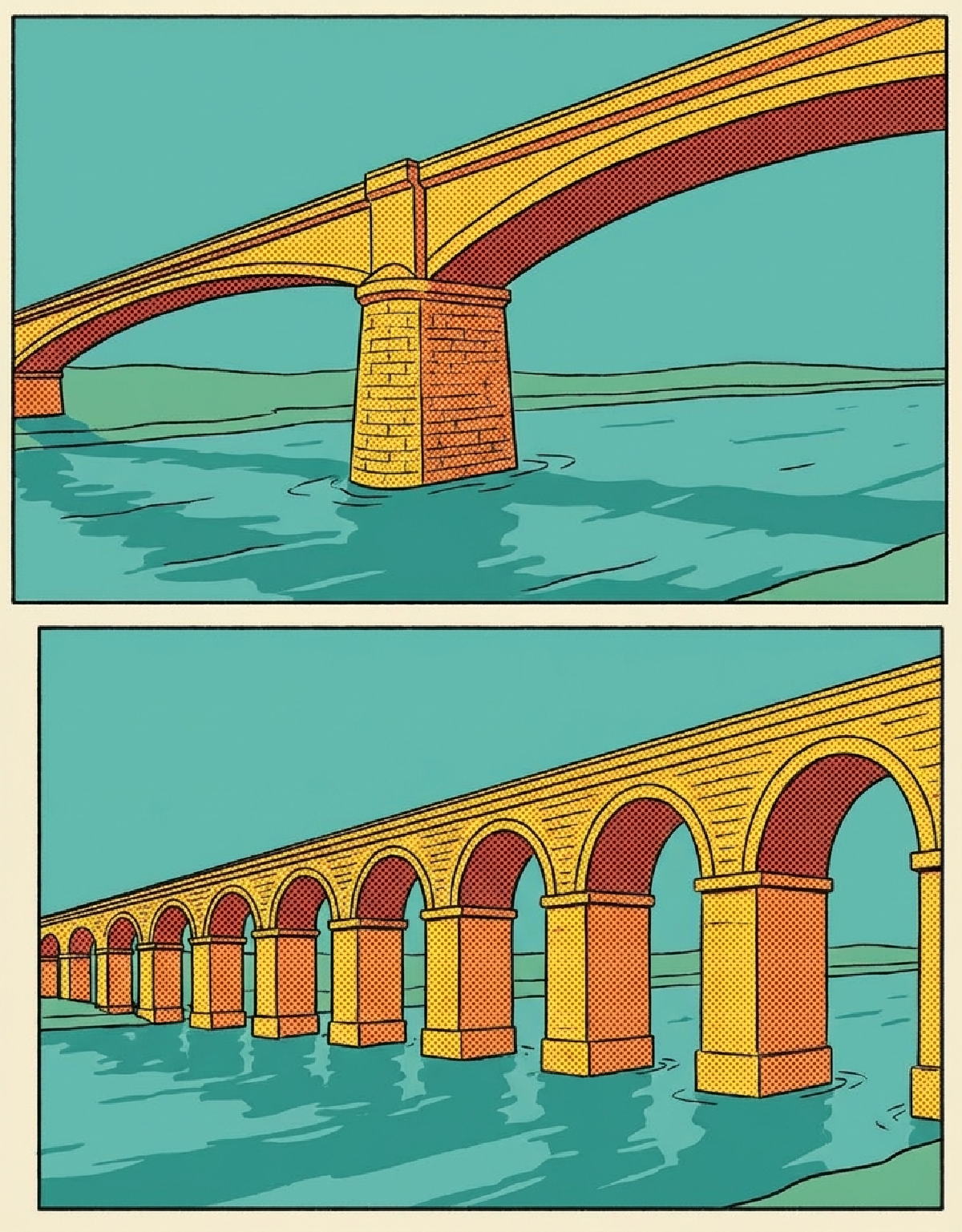

When we allow silos of knowledge to form, we create what systems theorists call a Single Point of Failure. In engineering, you would never design a bridge with a single support beam that, if compromised, brings down the whole structure. Yet we design our organizations this way constantly.

We assign the “finance guy.” We assign the “operations girl.” We let them hoard knowledge because it seems efficient in the short term.

But there is a hidden cost.

The person holding all the knowledge becomes a hostage to their own importance. They cannot take a vacation. They cannot get sick. They cannot be promoted to a new role because they are too valuable in their current one.

By trying to move fast, we inadvertently paralyze our best people.

Calculating Your Number

#So how do you calculate your Bus Factor?

You can do this with a simple audit.

List every critical function of your business. Payroll. Server deployment. Customer support escalation. Key account management. Investor relations.

Now, next to each function, write down the names of the people who can successfully execute that function from start to finish without asking for help.

If a name appears alone next to a critical function, circle it in red.

That is a failure point.

You might find that you, the founder, are the red circle next to almost every item. This is common, but it is not sustainable. It means you have not built a business. You have built a high-pressure job for yourself.

It is also worth looking at the “permission” layer.

Who has admin access to the servers? Who is the primary owner of the domain registrar? Who is the only signer on the bank account?

I once knew a startup that was locked out of their own website for three weeks because the only developer with the AWS root password had a medical emergency and was in a coma. The company bled money simply because they had not shared a password.

These are not technical problems. They are governance problems.

The Psychology of Hoarding

#There is a human element we must address.

Some employees, and even some founders, subconsciously enjoy a Bus Factor of one.

Being the only person who can solve a problem feels good. It provides job security. It feeds the ego. It makes us feel indispensable.

If I am the only one who can fix the server, then I am the hero every time the server crashes. If I teach you how to fix it, I am no longer the hero. I am just another employee.

We have to shift this cultural narrative.

We need to celebrate the teachers, not just the doers. In a healthy organization, the highest status should be awarded to the person who makes themselves redundant.

If you can document your role and train a successor, you free yourself to tackle higher-order problems. You make yourself promotable.

If you hoard knowledge to stay relevant, you stagnate.

Strategies for mitigation

#Once you have identified your risks, how do you fix them without doubling your headcount?

You do not need to hire a shadow for every employee. You can use lighter strategies.

The first is Pair Programming, or specifically, Pair Working.

This is a concept borrowed from Agile development where two programmers work on the same workstation. One types, the other reviews. They switch roles frequently.

You can apply this to business tasks. If you are running payroll, have someone else sit with you and watch. Have them drive the mouse while you give instructions. This transfers tacit knowledge—the little intuitive clicks and shortcuts—that never make it into formal documentation.

The second strategy is The Rotation.

Have your customer support lead swap roles with your sales lead for a week. Have your backend engineer handle frontend tickets for a sprint.

This is painful at first. Productivity will dip. Mistakes will happen.

But the cross-pollination is invaluable. It ensures that if one person goes down, there is at least one other person who has a vague idea of how to keep the lights on.

The third strategy is the “Vacation Test.”

Force your key people to take time off. And I mean real time off. No Slack. No email. No “call me if it’s an emergency.”

If the business breaks while they are gone, you have successful data. You now know exactly what is broken. You know exactly what knowledge was trapped in their head.

When they return, your immediate priority is to fix those gaps.

Pick the moment to do this and you prevent it happening “accidentally”. Better to be pushed offline at a time you select.

The Valuation Impact

#If you are building this company with the intention of ever selling it, the Bus Factor is a financial metric.

When a potential acquirer looks at your business, they are buying a machine. They want to know that the machine runs.

If they realize that the machine only runs because Dave in engineering knows where to kick the server when it hums, they will discount the price. They are buying risk.

They are terrified that once the acquisition closes and the golden handcuffs unlock, Dave will leave. And the asset they just bought will become worthless.

A high Bus Factor (meaning many people can do the job) increases the enterprise value of your company. It proves that you have built intellectual property and systems, not just a collection of smart freelancers.

It creates an asset that is transferable.

Building for Exit

#Even if you never plan to sell, you should build the company as if you are leaving tomorrow.

This is the paradox of leadership.

To lead effectively, you must constantly work to make your own leadership unnecessary in the daily operations. You must build a clock, not just tell the time.

When you lower the key person risk, you lower the anxiety level of the entire organization. The team knows that the ship will sail even if the captain is asleep.

So look at your list. Look for the red circles.

Pick one area where you are the bottleneck. Pick one area where a key employee is the single point of failure.

Start the transfer of knowledge today.

Because we never know when the bus is coming.