You launch your product.

You post it on social media. You email your friends. You get a flurry of signups. People tell you “congratulations.” They tell you the design is beautiful. They tell you it is a great idea.

You feel a rush of validation. You think you have done it.

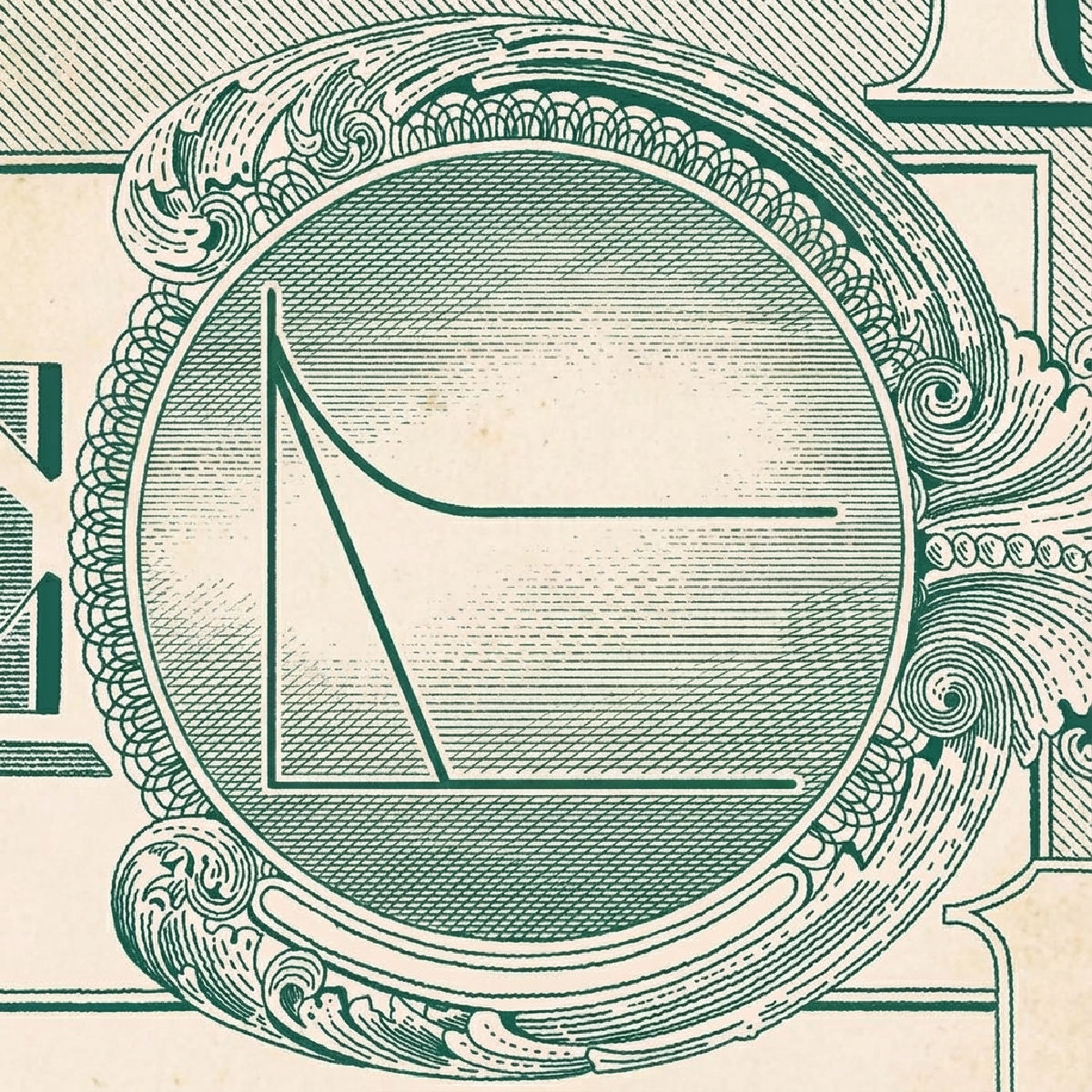

But three months later, you look at your retention graph.

It looks like a ski slope. Everyone who signed up on day one is gone. Your daily active users are approaching zero. The silence is deafening.

You are experiencing the “False Positive” of Product-Market Fit.

It is the most painful phase of a startup because it feels like success until it suddenly feels like failure. You confused the excitement of the launch with the utility of the product.

Product-Market Fit (PMF) is not a feeling. It is not a compliment from your mom. It is a mathematical reality where the market pulls the product out of you faster than you can build it.

Most founders never find it because they are too afraid to ask the hard questions that would reveal they don’t have it.

The Mom Test

#Rob Fitzpatrick wrote a book called The Mom Test, and its core premise is simple: If you ask your mom if your business idea is good, she will lie to you because she loves you.

This applies to everyone, not just your mom. Friends, colleagues, and even strangers want to be nice. They don’t want to hurt your feelings.

- If you ask, “Do you like this idea?” they will say yes.

- If you ask, “Would you buy this?” they will say yes.

These are lies. Not malicious lies, but social lies.

To verify PMF, you have to stop asking for opinions and start asking for commitments.

A commitment is costly. It involves reputation, time, or money.

If you ask a prospect for a meeting and they say yes, that is a time commitment. If you ask them to introduce you to their boss, that is a reputation commitment. If you ask them for a deposit, that is a financial commitment.

Until someone gives you something of value, you have nothing. You have a hypothesis, not a business.

The Sean Ellis Test

#There is a quantifiable metric for PMF that was popularized by Sean Ellis, the growth hacker who helped scale Dropbox.

It is a single survey question.

“How would you feel if you could no longer use this product?”

The options are:

- Very disappointed

- Somewhat disappointed

- Not disappointed

If 40 percent or more of your users answer “Very disappointed,” you have Product-Market Fit. You have built something essential. You have built a utility, not a toy.

If the number is below 40 percent, you are in the danger zone. You cannot scale. If you pour marketing dollars into a product with a 15 percent “Very disappointed” score, you are just filling a leaky bucket.

This test is brutal because it ignores the “Somewhat disappointed” crowd. In startups, “somewhat” is worthless. You need love, or you need hate. Indifference is death.

The Retention Flatline

#If you have a live product, the ultimate arbiter of truth is your retention curve.

Plot the percentage of users who return to your app over time. Day 1, Day 7, Day 30, Day 90.

In almost every product, this line will drop sharply at first. That is normal. People try things and leave.

But the question is: Does it flatten?

Does it hit a floor where a core group of users stays forever? Or does it trend slowly toward zero?

If the line flattens, you have PMF for that specific cohort of users. Your job is then to find more people like them. If the line hits zero, you do not have a product. You have a leaky sieve.

Founders often hide this reality by focusing on “top of funnel” metrics. They look at new signups. They look at total registered users. These are vanity metrics. They always go up (unless you delete accounts).

Retention is the only metric that matters for validation. It measures value delivered over time.

The Hair on Fire Problem

#Michael Seibel from Y Combinator often talks about the “Hair on Fire” problem.

If your hair is on fire, and I try to sell you a brick to put it out, you will buy the brick. You don’t care if the brick is ugly. You don’t care if the brick is expensive. You just want the fire out.

If you’re thinking, “why a brick?” then you should watch the video Why a brick?

This is what true PMF feels like. The customer has a problem so acute that they are willing to use a half-broken, ugly MVP just to solve it.

If customers are complaining about the font size, or the color of the button, or a minor feature request, they probably don’t have their hair on fire. They are engaging in “bike-shedding” because the core problem isn’t urgent enough.

When you have PMF, the server crashes and customers send you angry emails demanding you fix it now. When you don’t have PMF, the server crashes and nobody notices for three days.

The Pivot or Perish Moment

#So what do you do if you run the tests and the answer is “no”?

You have to be honest. You have to stop selling and start listening.

You have to go back to the customer discovery phase. You don’t necessarily need to throw away the code, but you might need to throw away the use case.

Maybe you built a project management tool for designers, but only the accountants are using it. Pivot to the accountants. Maybe you built a social network, but people only use the photo filter. Pivot to the photo filter.

This requires checking your ego at the door. You have to fall out of love with your solution and fall in love with the problem.

The market is never wrong. If they aren’t buying, you aren’t solving.

It is better to realize this today, with cash in the bank, than in twelve months when the runway is gone.

PMF is not a destination. It is a pulse check. You have to check it constantly. Because even if you have it today, the market moves. The fire might go out.

Keep the pulse. Keep asking the hard questions.

And don’t believe anyone who says “good job” unless they also hand you a credit card.