You open your phone in the morning and see the notification.

A competitor, or perhaps just a peer you met at a networking event, has just announced their seed round. They raised three million dollars. There is a photo of them smiling. There is a quote from a partner at a top-tier firm about how this company is going to change the world.

You look at your own bank account. You look at your slow but steady growth. You look at the problems you are trying to solve with limited resources.

And you feel like a failure.

You feel like you are moving too slowly. You feel like the market has voted and you have lost. You feel the sudden, desperate urge to build a pitch deck and hit the road to find investors.

But before you open PowerPoint, you need to pause.

You need to ask yourself a question that most founders avoid answering honestly.

Do you want the money because your business model requires rocket fuel to function?

Or do you want the money because you want a rich person to tell you that you are smart?

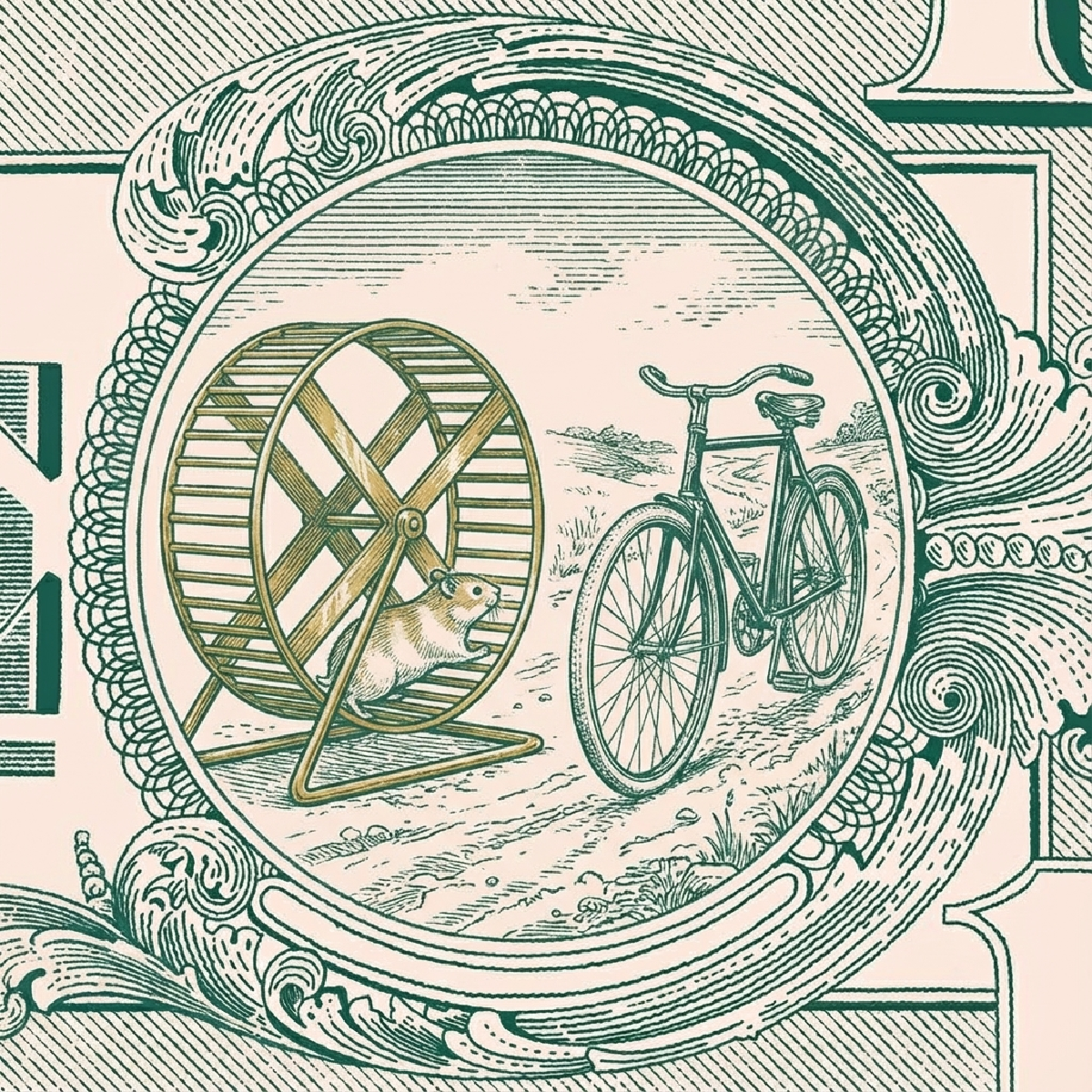

This is the investor dilemma. It is the confusion between capital requirements and emotional validation.

The Economics of the Home Run

#To understand if you should raise money, you first have to understand the business model of the people giving it to you.

Venture Capitalists are not banks. They are not loan officers. They are high-stakes gamblers playing a specific mathematical game known as the Power Law.

A VC firm might invest in thirty companies. They expect fifteen of them to fail completely. They expect ten of them to break even or make a small return. And they need one or two of them to return 100 times the investment to pay for all the losers and make a profit for their own investors.

This math dictates their behavior.

When a VC invests in you, they are not looking for a nice, sustainable business that generates two million dollars a year in profit. That is a failure to them. It does not move the needle on their fund. Even if it is life changing for you.

They need you to be a unicorn. They need you to grow at 300 percent year over year. They need you to either IPO or sell for a billion dollars.

If your business is not designed to grow at that speed, taking their money is a death sentence.

You will be forced to spend aggressively to capture market share. You will be forced to hire faster than you can manage. You will be forced to burn cash to show top-line growth, even if your unit economics are broken.

If you take the money, you are signing a contract to swing for the fences. And when you swing for the fences, you strike out a lot more often.

The Validation Trap

#So why do so many founders whose businesses do not fit this model still try to raise VC?

Because we are insecure.

Building a company is lonely. It is full of rejection. Customers say no. Employees quit. Products break. We are constantly plagued by the fear that we are delusional.

When a professional investor writes you a check, it silences that fear. It serves as a proxy for success. We think, “If this smart person who sees thousands of deals chose me, I must be right.”

But VCs are wrong all the time. In fact, based on the math we just discussed, they are wrong most of the time.

Fundraising is not a milestone of success. It is a milestone of obligation. It means you have successfully convinced someone to let you owe them a massive return.

The only true validation is revenue. The only vote that counts is the customer pulling out their credit card. If you have that, you do not need a VC to tell you that you are real.

The Loss of Optionality

#There is a hidden cost to capital that does not show up on the balance sheet.

It is the loss of freedom.

When you bootstrap, or self-fund, you are the dictator of your small nation. You can decide to pivot. You can decide to take a month off. You can decide to stop growing and maximize profit so you can buy a nice house.

When you take venture capital, you have a boss. You have a board of directors. You have a fiduciary duty to maximize shareholder value.

Imagine you build a company to ten million dollars in revenue. You are profitable. Someone offers to buy you for thirty million dollars. If you own 100 percent of the company, that is a life-changing outcome. You walk away with thirty million dollars.

If you have raised venture capital, the investors might block that sale.

Why? Because a thirty million dollar exit does not return their fund. They would rather you gamble the thirty million to try and turn it into three hundred million, even if it means risking the company going to zero.

Their incentives and your incentives are no longer aligned.

The Case for the Customer-Funded Business

#There is an alternative path that gets less press but creates more millionaires.

The customer-funded business.

This is where you sell a product or service, make a profit, and reinvest that profit into growth. It is slower. You cannot hire fifty engineers on day one. You have to be disciplined.

But the advantages are profound.

You retain control. You retain the equity. If you eventually get to ten million in revenue, you might be taking home two million a year in distributions. You own your destiny.

Furthermore, bootstrapping forces you to be honest. You cannot hide bad product-market fit behind a pile of cash. If the product sucks, you don’t eat. This forces you to fix the product faster than a venture-backed competitor who can afford to ignore churn for a few years.

When Venture Capital is the Right Choice

#This is not to say that VC is evil. It is a tool. And like any tool, it is perfect for some jobs and terrible for others.

If you are building a nuclear fusion reactor, you cannot bootstrap. You need hundreds of millions of dollars in R&D before you can sell a single watt of energy. And that means you need to have a planet shattering future revenue potential.

If you are building a social network where the value is the network effect, you need to capture the entire market before you can monetize.

If you are in a winner-take-all market where speed is the only defense against competitors, venture capital is the weapon you need.

In these scenarios, the risk of moving slow is greater than the risk of blowing up.

The Unknowns of the New Economy

#We are also entering a period of unknowns regarding capital efficiency.

With the rise of AI and automation, the cost to build software is collapsing. A team of three can now do what used to take a team of thirty.

This changes the calculus. Do we still need massive seed rounds to get to market? Or is the era of the “unicorpse” (a unicorn that dies) coming to an end?

It is possible that the next generation of billion-dollar companies will be built with very little outside capital. We do not know yet. But it is a question you should be asking.

Making the Decision

#So how do you decide?

Look at your roadmap. Look at your market.

Can you get to the first million dollars in revenue without outside help? If the answer is yes, do that first. The validation you get from those customers will be worth more than any check.

And if you do get to that million dollars, and you decide you want to pour gas on the fire, you can still raise money. But you will do it on your terms, with a working business behind you, and not just a pitch deck and a prayer.

Do not let envy drive your strategy.

Remember that the goal is not to raise money. The goal is to make money.