You remember the first time you made a real profit.

It felt incredible. You saw the bank balance grow. You felt the validation of the market. You thought about all the ways you could reinvest that money or perhaps take a nice bonus for yourself.

Then April arrived.

Your accountant sent you a PDF. You opened it. You stared at the number on the bottom line.

A wave of nausea hit you. You realized that a massive chunk of the money you thought was yours actually belonged to the government. You wrote the check. You watched the balance drop. You felt like you had been mugged.

This is a rite of passage for every entrepreneur.

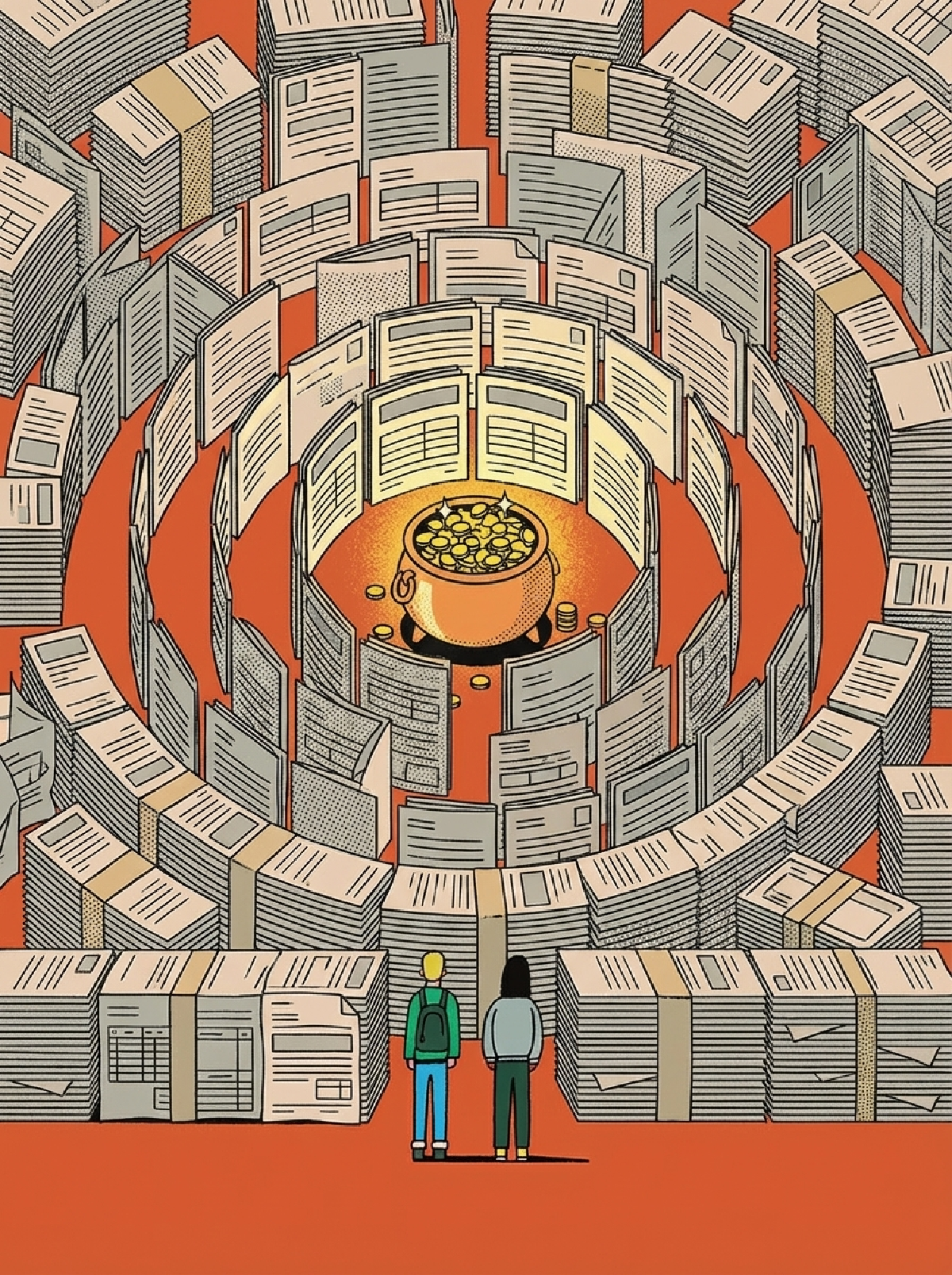

But for many, it becomes a recurring nightmare. We treat taxes as a natural disaster. We view them as an inevitable, unpredictable event that destroys our cash flow once a year.

We adopt the “Ostrich Strategy.” We bury our heads in the sand for eleven months, scramble to find receipts in March, and pay whatever the accountant tells us to pay in April.

This is a dereliction of duty.

Taxes are not a fixed bill like your rent or your server costs. Taxes are a variable expense.

In fact, they are often the single largest expense in your life and your business. To ignore them is to admit that you are okay with bleeding capital simply because you are too bored or too intimidated to learn the rules of the game.

The Architecture of Incentives

#To change your strategy, you must first change your philosophy.

Most people view the tax code as a list of penalties. It is a way for the government to take your money.

This is incorrect.

The tax code is actually a series of incentives. It is a tool for social and economic engineering. The government wants certain things to happen in the economy. They want people to hire employees. They want companies to buy equipment. They want founders to invest in research and development.

When you do the things the government wants you to do, they give you a tax break.

When you do things they do not care about, or things they want to discourage, they tax you at the highest rate.

If you simply take money out of your company as a salary and spend it on consumer goods, you are doing nothing for the economy other than consuming. Therefore, you pay the highest tax rates.

If you leave the money in the company and buy a fleet of trucks, you are stimulating the manufacturing sector. Therefore, you get a deduction.

Once you view taxes through this lens, the game changes. You stop asking “How do I hide my income?” and start asking “How do I align my spending with the government’s incentives?”

The Entity Decision

#The first and most critical variable is your corporate structure.

Many founders start as a Sole Proprietorship or a generic LLC because it is easy. It takes five minutes online. But this simplicity has a cost.

If you are an LLC, all the profit flows through to your personal tax return. You pay income tax on it, but you also pay self-employment tax. This is roughly 15.3 percent on top of your income tax. It pays for Social Security and Medicare.

If you make $100,000 in profit, that is a $15,300 bill just for the privilege of working for yourself.

By simply filing a form to be taxed as an S-Corp, you can change this math. In an S-Corp, you pay yourself a “reasonable salary” which is subject to that tax. But the remaining profit is taken as a distribution, which is not subject to self-employment tax.

This single piece of paper can save you thousands of dollars a year. Yet many founders wait years to do it because they are afraid of the paperwork.

On the other end of the spectrum is the C-Corp. For a small lifestyle business, a C-Corp often leads to double taxation. But if you are building a high-growth startup, the C-Corp unlocks the holy grail of tax planning.

Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS).

If you hold C-Corp stock for five years and meet certain criteria, you can sell that stock and pay zero federal capital gains tax on up to $10 million or 10 times your basis.

Imagine selling your company for $10 million and keeping the entire check. That is the power of structure.

The Timing of Cash

#The second variable is timing.

The tax year ends on December 31st. This is an arbitrary date, but it is a hard wall for the IRS.

If you make a sale on December 31st, you owe tax on that money in April. If you make the sale on January 1st, you do not owe tax on it for another fifteen months.

This creates an opportunity for “Cash Method” accounting strategies.

If you have a profitable year, you should look at your upcoming expenses. Do you need to buy new laptops? Do you need to pay for a software subscription? Do you need to pay a retainer to a marketing agency?

If you pay those bills on December 30th, you reduce your taxable income for the current year. You are essentially moving the tax deduction into the present.

Conversely, if you are about to send an invoice for a large project in late December, consider waiting a week. If you send it in January, the revenue falls into the next tax year.

You are not changing the reality of your business. You are simply managing the timeline to maximize your cash flow.

Corporations can define their tax period.

The R&D Credit Superpower

#There is a specific incentive that almost every tech startup overlooks.

The Research and Development (R&D) Tax Credit.

When founders hear “R&D,” they imagine scientists in white lab coats mixing chemicals. They think it does not apply to them.

But the IRS definition of R&D is much broader. If you are writing code to build a new software platform, that is R&D. If you are engineering a new physical product, that is R&D. If you are improving a manufacturing process, that is R&D.

This credit is not just a deduction. It is a dollar-for-dollar reduction in your taxes.

And here is the kicker. Even if you are not profitable yet, you can often use this credit to offset your payroll taxes.

Startups that are burning cash and have zero profit still have to pay payroll taxes for their employees. The R&D credit can wipe out a significant portion of that bill. It is effectively free money that the government is giving you to encourage innovation.

Yet, billions of dollars in R&D credits go unclaimed every year because founders assume they do not qualify.

The Historian vs. The Strategist

#To execute any of this, you need the right partner.

Most founders have a CPA who functions as a historian. You send them your shoebox of receipts in March. They look at what happened in the past. They fill out the forms. They tell you what you owe.

A historian cannot help you save money. They can only record the damage.

You need a strategist.

You need a CPA who meets with you in October or November. This is tax planning season. This is when you can still make moves. You can still buy the equipment. You can still set up the 401k. You can still change your entity structure.

Once the ball drops on New Year’s Eve, the game is over. The strategist knows this.

When you interview an accountant, ask them one question.

“When do we meet to discuss strategy?”

If they say, “We will talk when you send me your tax documents,” run away. You are looking for a partner who is proactive, not reactive.

We must acknowledge that tax law is complex and constantly changing. What worked last year might not work this year. There are unknowns regarding future legislation.

But the principle remains the same.

You have a fiduciary duty to your company to protect its capital.

Paying more tax than you legally owe is not patriotic. It is poor management.

So stop treating taxes as a bill you just pay.

Treat it as a line item on your P&L that you can manage, optimize, and control.

It is the one area of business where a few hours of study can yield a guaranteed return on investment.