You remember the early days with a specific kind of fondness.

It was likely you and two or three other people in a room that was too small. You were eating bad food and working impossible hours. There were no job titles. There were no departments. There was just a list of things that had to be done and a group of people willing to do them.

You had a person who wrote code in the morning, answered support tickets in the afternoon, and ordered office supplies in the evening.

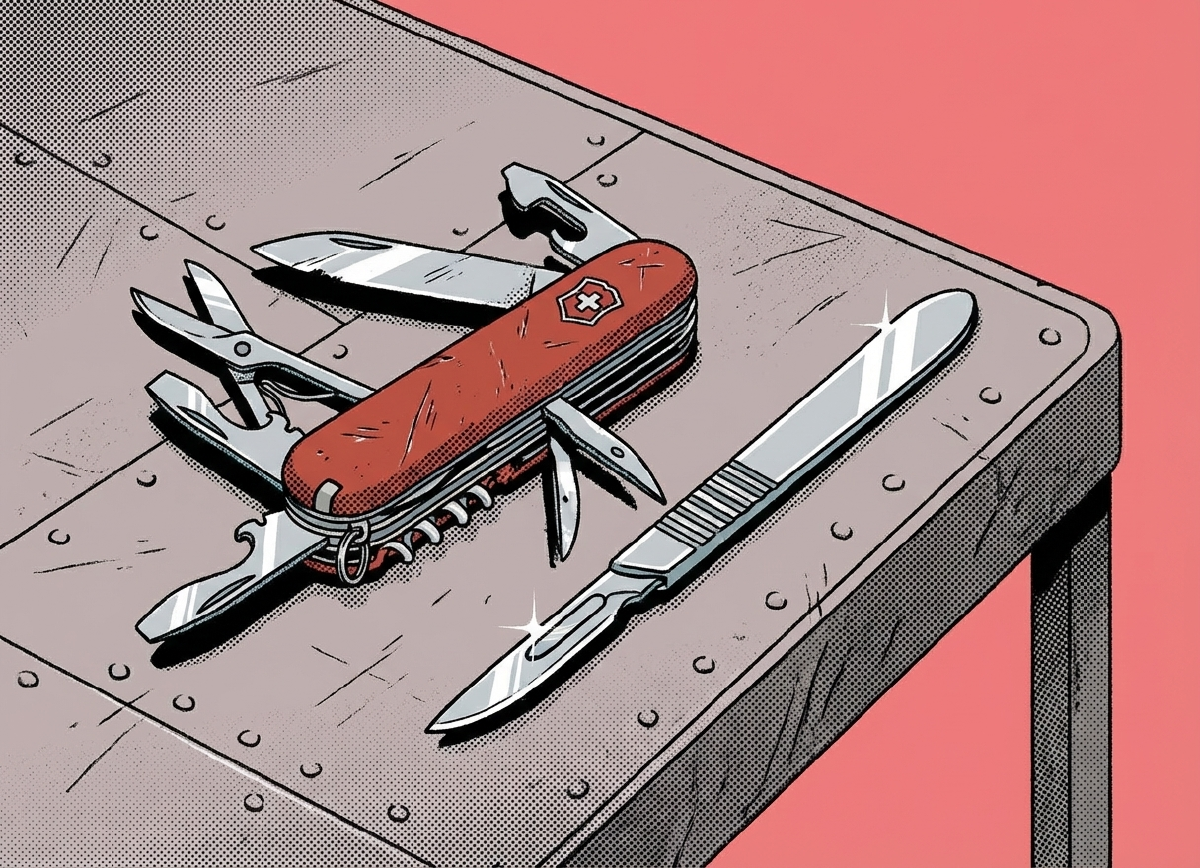

These people are generalists. They are the Swiss Army knives of the startup world. They are invaluable when you are trying to go from zero to one. They thrive on chaos. They love the fact that no two days are the same.

But eventually, the company changes.

The revenue grows. The customer base expands. The product becomes complex.

And suddenly, the very traits that made your team successful in the beginning become the bottlenecks that threaten to kill your future.

You are likely feeling this friction right now. You might notice that the person who handles your marketing is overwhelmed by the nuances of paid acquisition attribution. You might notice that your head of engineering, who built the prototype in a weekend, is struggling to manage a team of twenty developers.

This is not a failure of character. It is a failure of structure.

You have reached the point where you must undergo the Specialist Shift.

It is one of the most painful transitions a founder has to navigate because it requires you to look at the people you trust the most and admit that they are no longer the right people for the job.

The Utility of the Generalist

#To understand why this shift is necessary, you have to look at the mechanics of early-stage growth.

When you are searching for product-market fit, speed is your only advantage. You cannot afford to have a meeting about a meeting. You cannot afford to wait for a specialist to design a perfect process.

You need someone who can execute an 80 percent solution in four hours.

Generalists are optimized for this. They trade depth for breadth. They can speak enough design, enough code, and enough sales to keep the machine moving.

However, as a business scales, the penalty for mistakes increases.

When you have ten customers, a bug in the code is a funny anecdote. When you have ten thousand customers, a bug in the code is a PR disaster.

When you are spending five hundred dollars a month on ads, inefficient targeting costs you pizza money. When you are spending fifty thousand a month, inefficient targeting costs you the runway.

As the stakes rise, the margin for error shrinks. You can no longer survive with 80 percent solutions. You need 99 percent precision.

This is where the generalist hits a wall.

They cannot be an expert in everything. No one can. But because they have been doing everything for so long, they often feel like they should be able to handle it.

This leads to a dangerous situation where your loyal early employees burn themselves out trying to solve complex problems that are outside their depth.

Identifying the Breaking Point

#How do you know when it is time to make the switch?

It is rarely a single catastrophic event. It is usually a series of small frustrations that accumulate over time.

Look for these patterns in your organization:

- The Bottleneck: One person has to sign off on everything, but they do not have the technical knowledge to critique the work effectively. They become a rubber stamp or a roadblock.

- The Plateau: A department stops improving. Your sales process works, but conversion rates have been flat for six months. The generalist is maintaining the status quo because they do not know how to optimize it further.

- The Reinvention of the Wheel: Your team is solving problems that have already been solved by the industry. A specialist knows the standard best practices. A generalist tries to invent a new way to do payroll and gets it wrong.

When you see these signs, you need to bring in a Specialist.

This is someone who has done this specific job before at a higher level. They are not cheaper. In fact, they will likely be the most expensive hires you have made to date.

They do not want to wear multiple hats. They want to wear one hat and wear it perfectly.

The Cultural Friction

#Bringing a high-level specialist into a team of scrappy generalists creates immediate friction.

The generalists will view the specialist as slow. They will say things like, “Why do we need a three-page document to change a button color? We used to just do it.”

The specialist will view the generalists as reckless. They will look at the codebase or the CRM setup and be horrified by the lack of documentation and process.

You, as the founder, are the bridge between these two worlds.

You have to explain to the old guard that process is not bureaucracy. Process is the infrastructure that allows you to move fast without breaking things.

You also have to explain to the new specialist that the chaotic mess they inherited is the only reason the company exists to pay their salary.

There is a specific danger here that you must watch for. It is the “Ivory Tower” effect.

Sometimes, specialists come in and try to implement the exact playbook from their previous company—usually a much larger corporation—without adapting it to your current stage. They try to build a Google-level infrastructure for a Series A startup.

You need specialists who are builders, not just maintainers. You need people who have deep domain expertise but are still willing to get their hands dirty.

The Human Cost

#What happens to the generalists?

This is the question that keeps founders awake at night.

You have a few options, but none of them are easy.

Option 1: They Scale Up Sometimes, a generalist has the potential to become a specialist. They might decide they love Product Management and want to stop doing Customer Support. If they have the aptitude, you can mentor them. But this takes time you may not have.

Option 2: They Move Down You hire a VP above them. This is often a blow to the ego. The person who reported directly to you now reports to the new hire. If the generalist is humble and eager to learn, this is a great outcome. They get to learn from a mentor. If they are ego-driven, they will likely quit.

Option 3: They Move On Sometimes, the company simply outgrows the person. The skills that were vital at the seed stage are irrelevant at Series B. It is better to have an honest conversation and help them find a new role elsewhere than to keep them in a position where they are destined to fail.

There is no perfect way to handle this.

It will feel like a betrayal of the early bond you formed. You will feel like you are becoming “corporate.”

But you must remember why you are here.

You are not running a social club for your friends. You are building an entity that needs to survive and thrive in a competitive market.

If you protect the feelings of your early team at the expense of the company’s performance, you are putting the livelihood of every other employee at risk.

The Specialist Shift is inevitable if you are successful.

It means you have built something complex enough to require experts. It is a sign of victory, even if it feels like a loss.

Look at your org chart today.

Identify the boxes where “good enough” is no longer good enough.

That is where you need to make your next hire.